They plunge to the bottom of the frozen sea, holding their breath, blinded by the murky abyss, searching not only for pearls, octopi or abalone, but also for freedom.

What would happen if their line were to break? Would the men comfortably sitting above in their boats, gleefully singing songs, try to save them? It doesn’t matter. The Japanese Ama defy the ridged confines of gender expectations because they are driven by a unified sense of purpose – to live free.

For the Ama or “women of the sea”, their faith is not in men but in nature. After all, the sea itself is an intoxicating female entity. Its creatures are the Ama’s allies. Their destinies are woven together like a fluid tapestry.

As the divers rise back to the surface and slowly exhale, the bay rings with the whistling echoes of their gentle gasp, and with it, reverberations of strength, autonomy, courage, stamina, and beauty.

The Ama are one of the most interesting elements of Japanese society. They are the female divers who, since about the year 750, have been diving for pearls, abalone, octopi, and lobsters, as well as harvesting seaweed along the coastline of Japan.

There are many fables of the Ama, including the story of Princess Tamatori, depicted in a Japanese block print from 1814 titled The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife, by Hokusai. It is an example of Japanese erotic art called Shunga, popularized during the Edo Period. The divers were often represented as erotic, simply because in Japanese culture the sea is seen as a female entity.

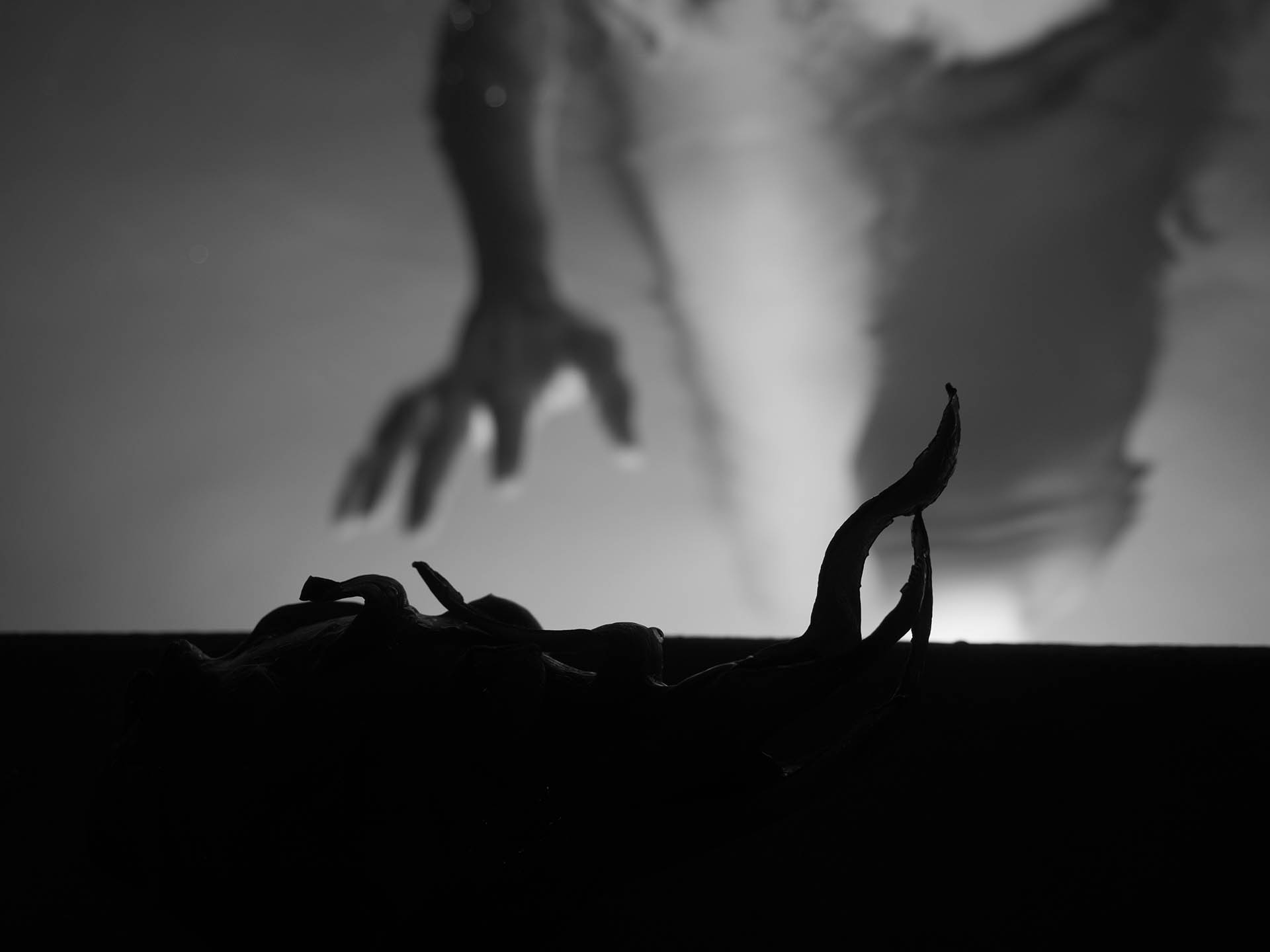

It is believed that the print depicts the story of Princess Tamatori, a figure highly popularized during the Edo period. The princess was a modest shell diver or Ama, who was searching for a pearl stolen from her husband’s family, the Fujiwara Clan, by Ryujin, the dragon god of the sea. Vowing to find the jewel Tamatori dives down to Ryujin’s underwater palace and is pursued by the god and his army of sea creatures, including octopi. When she finds the pearl, she cuts open her own breast and places the jewel inside; allowing her to swim faster in her escape. After reaching the surface the wound proves fatal, and in her death she is forever viewed a heroine.

The Ama were and still are, women who sought independence and community. There are many Ama who continue to dive passed the age of 90. It is one of the few professions dominated by woman and where there were no restrictions on their freedom.

Men would occasionally dive, but it was thought a better job for women, as it was believed that women had an additional layer of fat to keep them warm in the frigid waters. The original Ama would dive nude wearing just a loincloth and a protective scarf on their head. Streamlining their bodies in this way allowed them to swim faster and it was easier to warm up without wet clothing clinging to their skin.

An experienced Ama diver could dive as deep as 30 meters and hold her breath for up to two minutes at a time. These courageous women would dive from rocks, the shoreline and boats, with rope strung around their waists, and men would wait in the boats above to pull them back to the surface.

The whistling noise that they emit when resurfacing is called “Isobue”, or “ocean whistle,” which helps regulate their breathing. At one time, their whistling echoes would fill the bays of Japan. The entire free-diving process allows Ama to develop an extremely large lung capacity — a characteristic that many then pass on to their children.

In the 11th Century a noblewomen, Sei Shonagon, wrote The Pillow Book, a collection of her observations. She had encountered the Ama during her travels: “ One wonders what would happen to them if the cord round their waist was to break.” She goes on, “the men sit comfortably in their boats, heartily singing songs…they do not show the slightest concern about the risks the woman is taking”.

Even though socially the Ama’s labor was certainly less valued than that of men, they were unique among the female population. During a time when women were considered the subjects of men, a woman that could earn her own living, and also dictate the migration of her entire family, was unequivocally liberated. Their positions in society existed on almost a surreal plain.

The Ama are inspirational to me, as an artist and a woman, for many reasons, but foremost because what they did was just what they had to do, regardless of risk or reward. Even more remarkable to me is how they did it; breaking traditional rules within the confines of an existing system and still preserving their individual authenticity along with the connection to their culture.

My series, Whistling Echoes, explores the mythology of these women. Through the use of metaphor and symbolism, my visual interpretation explores the relationship that these women had to the sea and it’s creatures and how it not only shaped their destiny but also allowed them to live free.

Donna Garcia is a Fine Art Photographer from the United States.

To see more work and get more information on the artist please have a look at her Website or Instagram.

About Author

Latest stories

CommunityDecember 31, 2020We Bid Adieu

CommunityDecember 31, 2020We Bid Adieu Alexandra PrestonDecember 31, 2018December Wishes from Grryo

Alexandra PrestonDecember 31, 2018December Wishes from Grryo StoriesMarch 11, 2018The Marigoldroadblog Project by Adjoa Wiredu

StoriesMarch 11, 2018The Marigoldroadblog Project by Adjoa Wiredu Antonia BaedtDecember 22, 2017‘Tis a Jolly Grryo Christmas

Antonia BaedtDecember 22, 2017‘Tis a Jolly Grryo Christmas