I mostly photograph in a big slum, the largest Muslim slum, in Calcutta. Narrow alleys, no wider than the width of one person, separate little houses.

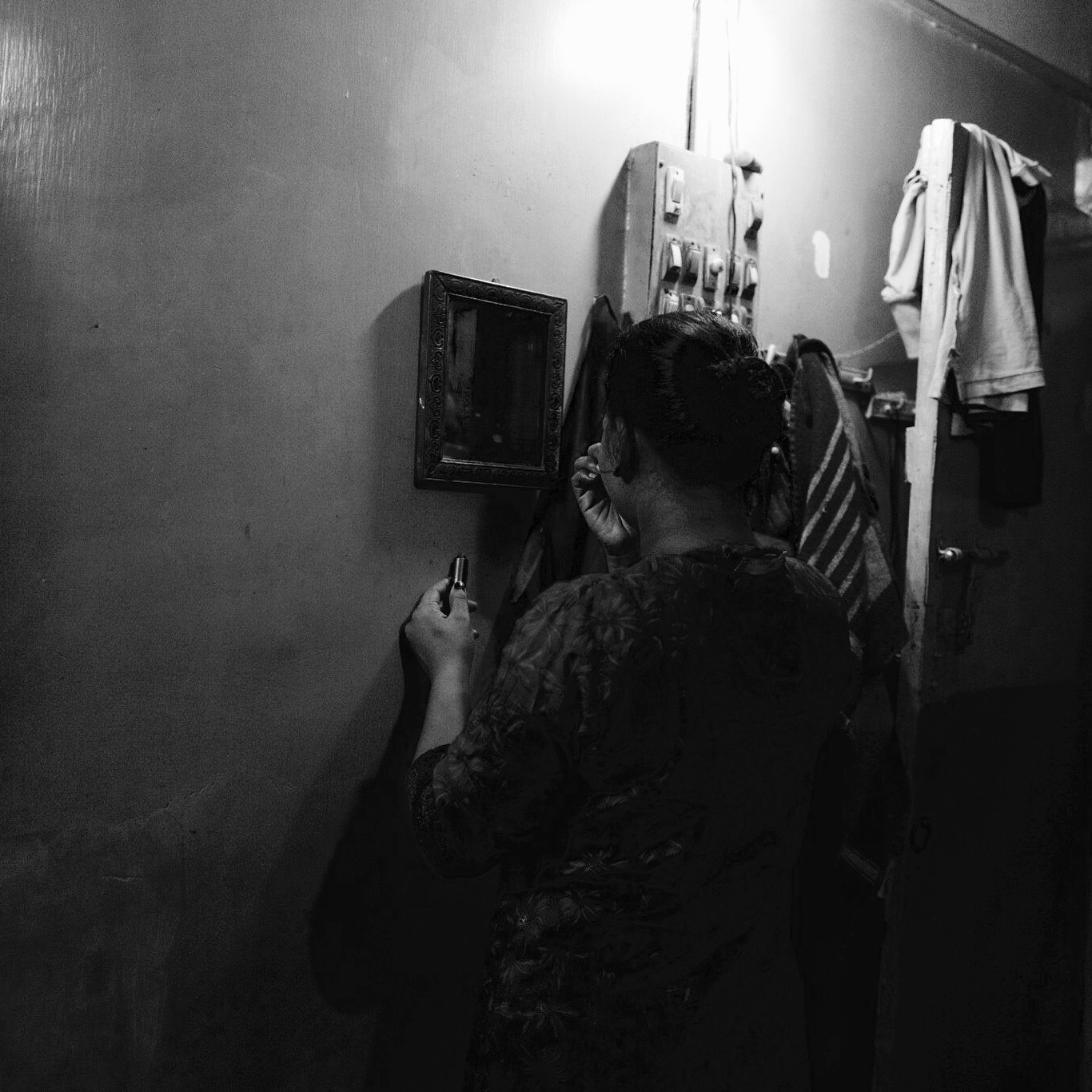

There are no doors to these houses, only curtains. The alleyways are dark, even at night, only a light shining through a half open window might show the way. I stand in dark corners and photograph women at the counter of stores, or the visible legs of a man, sitting by the entryway of his home, behind half parted curtain.

I photograph lit windows, or passageways through which you see a broken chair, a wooden cot–parts of a home. These images contain all the possible stories I’d never know and lives I’d never live.

I am, by nature, shy. I don’t generally start conversations with strangers; a ‘people-person’ is not quite the accurate description for me. The camera is my buffer against the real world. It allows me to, in a sense, permeate through that curtain—that flimsy cloth of privacy— without really being noticed.

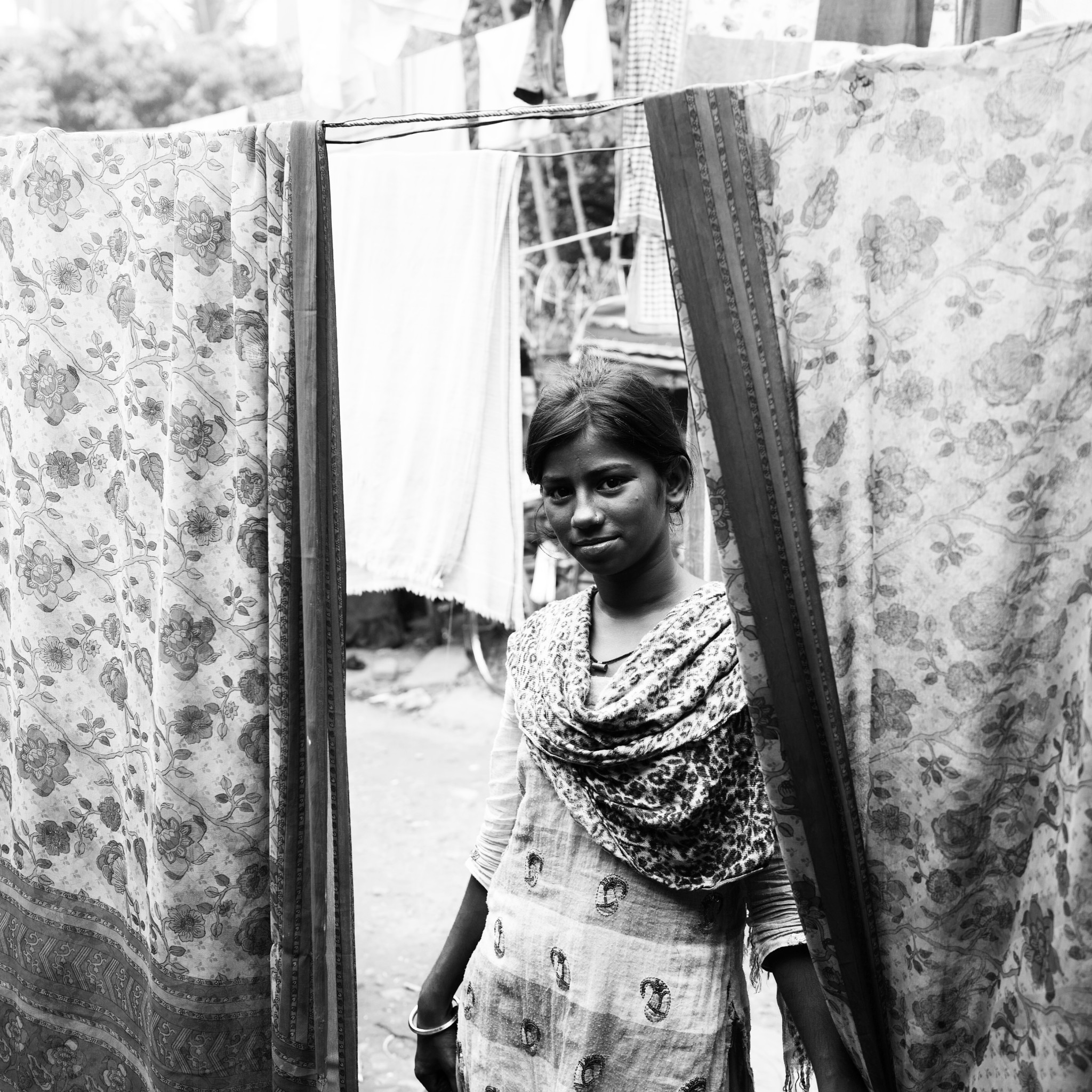

When I traded in the iPhone for a real camera, however, it was hard to go unnoticed. I was visiting the slum almost daily. My rolled up jeans and careless coiffure made me inevitably stand out from the sari and salwar clad women of the area. Soon the little children were pestering me to take their pictures. Women would push each other in front of my camera. Take a picture of her. Take a picture of her. Sometimes I would acquiesce.

Will you come to my house? A woman asked.

I was standing by a tea stall sipping chai. Mapping out my walk for the day. She pointed towards an alley beside a large construction site. A small shack, made of canvas and plastic stood at its corner, separated from the construction site by six feet of bamboo fence.

Will you come and take photographs of my house? You see, I have lived there for twenty five years but they are making me move.

She led the way and I followed.

The only furniture in the house was a large bed, a wall cabinet mounted on top of it and an iron cupboard in one corner. Clothes, enviably folded, were stacked neatly in a corner. Steel crockery shone from the cabinet. I took several pictures and in a few days, I returned to give her the prints.Then came more photo requests from others near by, more prints and more visits- a still ongoing cycle.

Invariably I’d be invited into someone’s home for tea, or to photograph a family gathered on the bed. These were strangers’ homes, homes of people with whom I’d have no connection with were it not for the camera. As someone who writes fiction, I had previously no intention of being a documenter of lives. Yet here I was, now the chronicler of the people of Park Circus Basti.

They were almost identical, these homes. Single rooms, no larger than a 100 sq. ft, where a family of four or more lived. On one end was always a big double bed. Sometimes, an old grandfather would be reading on it, sometimes, a young child sleeping, a scarf covering her face from the light. Those awake, sat on the floor watching television—mounted on the wall. A young girl might have been studying for her school. Every detail of their lives completely visible to me.

The camera, my wall against the world opened up a new form of intimacy between the slum dwellers and myself.

Portraits in themselves are an intimate form of photography, one I can’t say I’m very adept at. The very act of being photographed says—here is a record of me. And by recording it, a private moment has been exposed.

Portraits, by nature, unlike street photography, which is what I prefer to do, require a closeness between the photographer and the subject. A physical closeness, because you have to get closer to the subject…

…and the other kind of closeness- intimacy. A photographer sees his subject with a certain eye and he tries to capture a moment which speaks to him of what he sees. There is a connection, an interaction between the two— an intimacy that is recorded in the picture. and then exposed to the public.

A portrait is a dichotomy of the intimate inner and exposed outer. What is visible: the way one holds a cigarette, or slouches their chin when they are asleep and what can only be imagined: who was that woman peering out from the saris, hanging up to dry? She looks so enchanting. I must capture that. And that ‘that’ is what the photographer tries to create an intimacy with his subject for, to replicate in image.

As I wander through the traffic-less alleys, I cannot but help but think that no middle class or upper class home in the city would do such a thing—invite a stranger in, expose every little detail of what goes on behind closed doors.

I’m accustomed to an aunt visiting unannounced, or sweets sent across from a family friend. In India, we always keep doors open, in that sense. But there are always barriers: guests sit in the living room; if someone is sleeping, the bedroom door is always shut. As far as class is concerned, the barriers are even more rigid: a worker always stands outside the room; the gardener is never allowed to enter the house. But the people of Park Circus Basti keep their doors unabashedly open.

Contact:

Instagram: @bukusarkar

Web: www.bukusarkar.com

About Author

Latest stories

CommunityDecember 31, 2020We Bid Adieu

CommunityDecember 31, 2020We Bid Adieu Alexandra PrestonDecember 31, 2018December Wishes from Grryo

Alexandra PrestonDecember 31, 2018December Wishes from Grryo StoriesMarch 11, 2018The Marigoldroadblog Project by Adjoa Wiredu

StoriesMarch 11, 2018The Marigoldroadblog Project by Adjoa Wiredu Antonia BaedtDecember 22, 2017‘Tis a Jolly Grryo Christmas

Antonia BaedtDecember 22, 2017‘Tis a Jolly Grryo Christmas

Wonderful reading , brilliant images! Thank you deeply Buku for this amazing contribute

Thank you.

Thank you so,so much for sharing this.

The article was beautifully written, the images haunting, and have left me speechless, but deeply inspired.

I am blown away by this article. Thanks for sharing with us!

Thanks so much, Jeff.

Good stuff.

Wonderful. Beautiful writing and ecellent photography!1 Carry on!