In Spirit and Truth: An Interview with Laura Valenti by Romina Mandrini

A couple of years ago I enrolled in a six-week online photography course that would impact me – both as a person and as an artist – in ways I never could have imagined. This workshop not only challenged a lot of the pre-conceived ideas I had about photography and art making, but was also the impetus behind a profound journey of self-discovery.

The course was Candela: Finding Inspiration Through Photography, and it was taught by Laura Valenti. Laura is a photographer, curator and educator from Portland, Oregon. She is also the Outreach Director for Photolucida, a non-profit organization that aims to build connections between photographers and the gallery and publishing worlds.

Recently, I had the pleasure of asking Laura a little more about herself, her work and her philosophy.

As a child you lived in Asia. Tell us a bit about your cultural background and how you grew up.

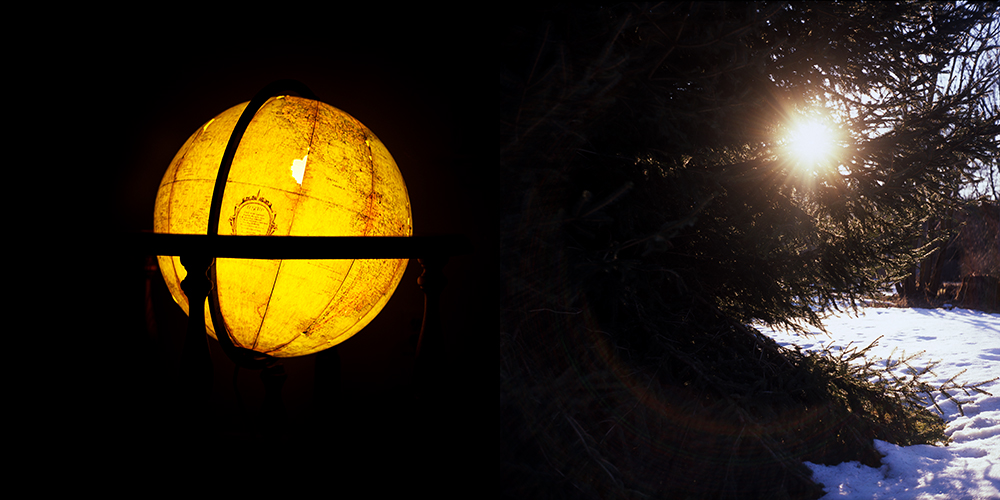

I spent my first fifteen years in Korea, Japan, and Hong Kong. Because I had such a transient childhood, it took me a long time to develop a sense of place like many other people have. I didn’t have roots in any particular place. My family used to say, “Home is where the furniture is!” It wasn’t uncommon for us to wake up in the middle of the night and not remember what country we were in, or what the house around us looked like. Over time, I learned that I do have a sense of place – I just carry it with me wherever I go. This concept has made its way into my photographic work, actually. I often photograph scenes that express a sense of home, comfort, and belonging.

What attracted you to photography in particular, as opposed to other forms of art making?

I really don’t know what drew me to photography, though I’ve always had a penchant for artsy, crafty endeavours. My father had a darkroom in the basement, so I was lucky to see the magic of the process at an early age. I know I desperately wanted my parents’ camera when I was very small. I keenly remember my mother allowing me to use it one day when I was five years old, and I remember taking my very first picture. I took pictures when we were out and about in Seoul, I photographed friends at birthday parties, and I set up my stuffed animals in silly little tableaus. The camera shot square images and came equipped with exciting flashcubes. Today I still shoot square format, so you could say I’ve stayed true to my original vision.

You have a deep interest in the intersection of mindfulness and the creative practice, and your focus is very much on the process itself rather than the end product. What are some of the ways in which you apply mindfulness when you are photographing?

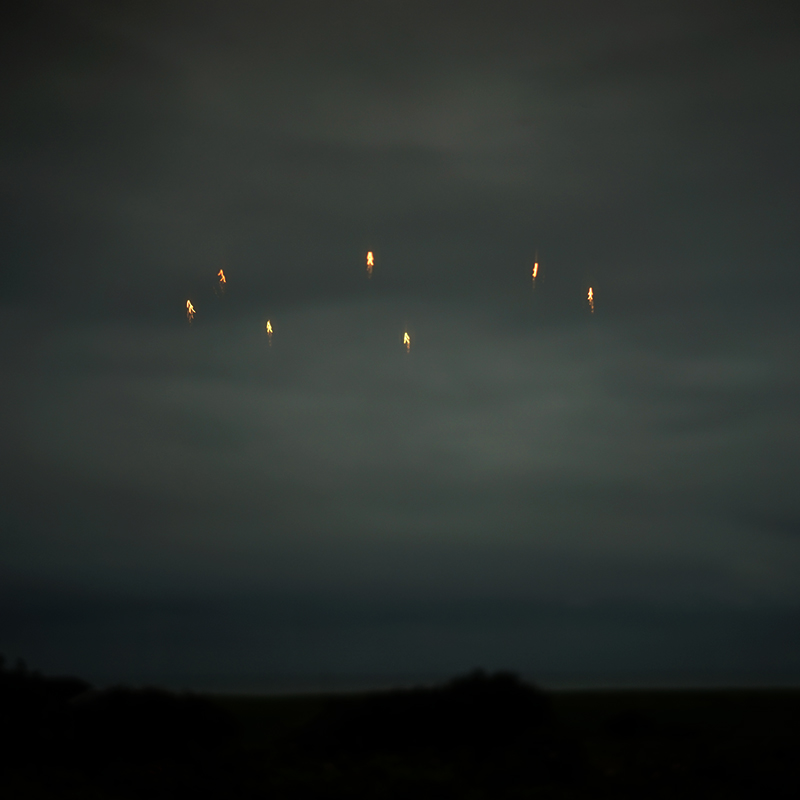

Mindfulness and the creative practice are interrelated in so many ways. It’s been said that mindfulness is about deepening the quality of our attention, and photography definitely does that. As a practice, photography can help us to be present. When we look around the world for interesting subjects, hone in on particular compositions, and thoughtfully set our cameras – that can all be an opportunity to slow down and practice mindfulness. Photography can be a meditation, in a way. So yes, process feels very important to me. I also like to use joy as a metric when photographing. Are your process, technique, and subject making you joyful? If so, you’re doing it right. A joyful, enriching process leads to stronger images.

How does your spiritual practice influence your work?

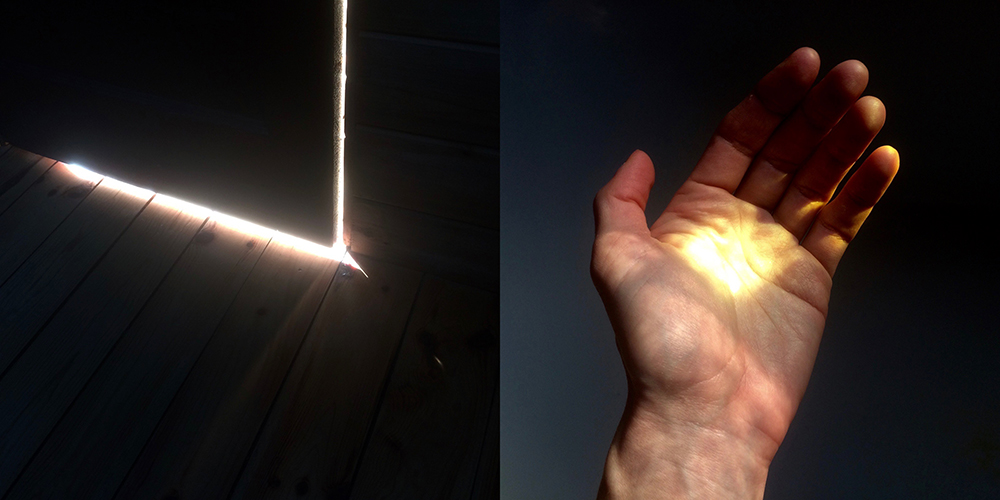

A lot of my images are an investigation of the idea of impermanence – a core Buddhist concept. When I recognize how fragile life is, it makes me appreciate it so much more. So, I make images to celebrate my body as it changes, to celebrate the beauty of changing light, to honor transient, transformative moments, and also to mark times when I feel particularly connected to my experience. I like images that are underpinned with depth of meaning like this.

Through my images, I’m also exploring how exquisitely beautiful, painful and joyous life can be – often all at the same time. Even awful experiences are occasions for insight and growth – and the creative process can be a cathartic way to come to terms with challenging life experiences.

One of the concepts that impacted me the most when I took your course was the idea that all photography is essentially an exploration of self. Was there a particular moment in your life when you distinctly realised this?

When I was nineteen I taught darkroom one summer to a group of “at-risk” teens through a great program called Youth In Focus. The kids photographed their home lives, and I remember seeing some pretty edgy pictures. But, the pictures were much more emotionally powerful than they would have been if they had photographed scenes they had no personal connection to.

When I curate exhibitions, I’m always most drawn to images that show the personality of the artist. I want to see artists really put themselves on the line to make their work. I want to see images that are vulnerable, open, emotional. When people make photographs that are deeply informed by their immediate life experience and emotions, they’re almost always stronger. That’s not to say that all photography should be explicitly autobiographical, but I do think images should reflect the passions and personality of each artist. Who you are matters.

Writers are often told to “write what you know”. It’s good advice for visual artists, too. We have backstage passes to our own lives, essentially. Of course, it can be scary to photograph from a place like this, but when photographers realize their photographs are less about the external world and more about their internal climate (and how they relate to the world), their work gets much more interesting.

A very good example of this, of course, is your series “The Family Home”, in which you pay homage to the house your father grew up in. Can you tell us a bit about this body of work and how it came about?

My grandfather died and his wife was preparing to sell the home. I went back, knowing it would be my last visit. It was a special place for me. I moved every couple years as a child, but visited that house almost every summer. So, it was a nostalgic, significant spot. I wanted to make images that honoured the place and my memories.

It was also a sad place, because the neighbourhood was a “cancer cluster”. Something was wrong that caused an inordinate number of people in the neighbourhood to get cancer. It affected my family too. I wanted the images to touch on the pain of loss as well as the beauty of nostalgia for home. I’m so glad I did the portfolio, since it’s my only tie now to those rich childhood memories.

As a juror and curator, you are constantly surrounded by other photographers’ images. Do you ever feel this gets in the way of your own ideas and style?

I really enjoy looking at a lot of work. It feels like a privilege to regularly be exposed to such a wide diversity of contemporary photography. It keeps me visually educated and inspired. Surprisingly, I don’t get visually overloaded, even when jurying a competition with 1000 entries. If anything, looking at a lot of work makes me feel like a stronger photographer. It gives me a better sense of what I like and don’t like, greater confidence in the direction of my work, and a fuller awareness of what is truly unique in the photo world (and what is overdone). When photographers are unaware of these things, it shows. Visual literacy is critical. Photography is like a language. We can express simple ideas with a basic grip on the syntax, and we can express more complex ideas (even poetry!) with a more fluent, nuanced understanding.

Finally, what makes a great photograph?

I care more about meaning and emotion in a photograph than about its technical perfection. I’m interested in images that really make me feel something. Technical mastery is important, of course, but if the image lacks emotional power, it just falls flat.

Most photography education focuses on the technical, and photographers are often taught that they need a lot of fancy gear and an exhaustive knowledge of post-processing programs in order to make images worth caring about. That’s just not true, and I think this prioritization of technique over vision does a disservice to photographers.

Photographers who just study technique for years and years often wind up feeling like they’ve missed some of the magic and beauty that sparked their interest in photography in the first place. Technical education can feel soulless after a point – but the arts are bursting with vibrancy and soul. So, I’m interested in opening up this conversation when I teach. I’m interested in talking to photographers about moving beyond the technical and doing the deeper work, investigating what it really means to be an artist. That’s the way to set the stage for great images.

You can find out more about Laura’s online courses and in-person retreats – as well as see more of her work – by visiting her website (www.valentiphotography.com). You can also find Laura on Fcebook and Instagram.

About Author

- Romina is a fine art photographer from Sydney, Australia, where she lives with her husband and four children. In her process, she has been amazed to find that all photos are, in fact, self-portraits, and within her images she continues to discover stories that she had long forgotten.

Latest stories

Romina MandriniDecember 21, 2016The Gift of Receiving

Romina MandriniDecember 21, 2016The Gift of Receiving Romina MandriniJuly 12, 2016In Spirit and Truth: An Interview with Laura Valenti

Romina MandriniJuly 12, 2016In Spirit and Truth: An Interview with Laura Valenti Romina MandriniMay 9, 2016Through the Looking Glass by Romina Mandrini

Romina MandriniMay 9, 2016Through the Looking Glass by Romina Mandrini