by Sam Smotherman | Jun 6, 2014 | Stories

A retrospective: The 24 Hour Project by Sam Smotherman

What’s it like to shoot street photography for a day? You walk a lot of miles. You miss shoots, you get frustrated with the misses, you smile about the gems. I’m not talking about a work day of 8 hours, but a full 24 hours straight.

Here is a story of my 24 hours shooting the streets of San Francisco.

My imagination is good enough to make the short flight from Los Angeles to San Francisco an uncomfortable one. So starts a few days of little rest, a world to monitor, and a city to shoot. I was challenged to shoot a new city by fellow 24 Hour Project participant Vlad, as he would be shooting SF for the first time this year also. The night flight on Thursday turns into early Friday morning conversations. A short rest and a couple of morning naps. I hit the street taking the train from south SF into the city proper.

Not to miss any opportunities to shoot in the city, I head to a photo walk for The Hundreds lead by SF Street Photographer Travis Jensen and Hundred photographer Van Styles. The photo walk starts around 2 and logs about five miles from China Town to the Fairy building. With the group starting from and swelling to over 80, then dwindling to about ten. The SoS Mobb. We head to Mission. I am able to rest for a few, catching a nap about for 20 minutes.

It’s near 9 o’clock Friday evening. In three short hours, my time starts – my 24 hours in SF.

The world has already been at it for hours. Starting in New Zealand, who are now deep into the project. I’m checking the feed @24HourProject. Excitement growing. The plan of where we are going to shoot and when still hasn’t been made. When we have a rough sketch with input from the SOS Mobb, @vladadat and I head out.

From the Mission, we head to the Castro. Easy place to start off. Lots of people and lots of light. A good place to start things off. I start things off asking IIldio to take her picture – she asks me to watch her bike while she gets a pastry. The Castro proves to be what we thought; pedestrians, club goers, and light. The evening has starting off well as we head back to the Mission for the second hour.

I found some good light with an outside Torta place off 16th. Something I would be looking for all day and especially during those dark hours. Now clubs and bars are closing. The great last debates, challenges, offers and promises are made – few want to go home alone. Vlad and I have our own challenges as we work with a group of women to get their pictures. The men who were hanging around them tell us to leave, but when they step a few feet away we grab a few and head to the car.

Vlad is a man who likes to challenge himself. “I’m only going to be taking square shots using the native camera,” He tells me as we drive off, feeding our phones as we head to North Beach where the scene lasts a little later than most of the city. “I don’t use a GPS. I’m trying to learn the city.” With a full 24 hours of challenges Vlad keeps pressing to do better.

North Beach was more sparse than I had expected. We decide to stop and have the first meal of the day. Pizza. After food I get my next shot – a woman who works next to the pizzeria lets me take her pic, Kimber. I’m already bad with names and so when I hear a new ones, even if simple, it takes me a while.

We walk around the area for a while. Crossing the street is an elderly gentleman who doesn’t want his picture taken but promises that if we come back tomorrow, he can shine our shoes. A shine that will keep for 3 months. I would have rather had a nice portrait of him, and I was wearing sneakers.

Vlad strikes up a conversation with a man in a doorway. Interesting man. A Vietnam vet, who’s been in the city since his war ended. He insists that we use our phones to take his picture and is reluctant to have me use my Canon DSLR. He’s also reluctant about telling me his name and offers two possibilities, Jim was one, but I forget the other one. He gets disappointed at me several times when I don’t get his references and jokes. He was a quick witted man for someone standing out in a doorway a 4 AM. He asks me to take his picture with his glasses on. “But I need to be reading something…like a newspaper.”

“Like that one?” I ask, pointing to one bag with a newspaper sticking out of of the top.

“Oh Yes.” he says, picking it up and then pretending to read.

He allows me a few shots with my DSLR and I feel bad when we have to move on, cutting the conversation a little shorter than I would have liked.

While the 24 Hour Project is one project, there are 24 deadlines, and participants are to post one picture per hour to a social media. One can’t rest on the shot they just took. You need to keep moving. Keep pushing. This sometimes leads you to post a shot that is not the best in the hour, but it’s a place holder. But for me when it was posted that was it, that hour had been covered. Still working on getting a better shot but the pressure was off until the top of the next hour. Having done this for 3 years I have some strategy about when to post and use the time to decompress.

From North Beach we head to the Harbor, I think. Somewhere near the water and boats. It’s a little more suburbia here. Most people inside, few buses or cars out but we hear music. We walk towards it. It keeps moving, further down the road. We talk to a night manager at a hotel who is also out looking for the source of the music. On the job at 5 AM dealing with complaints, no doubt.

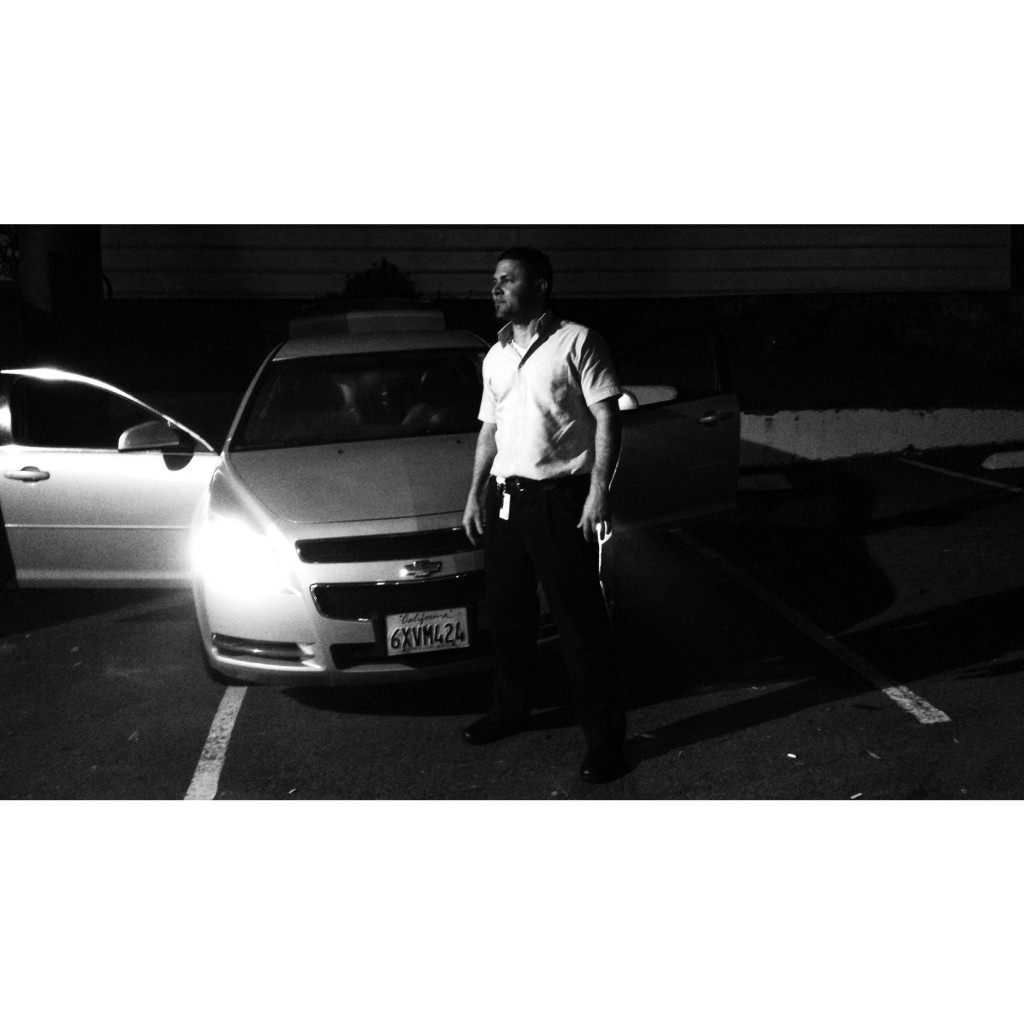

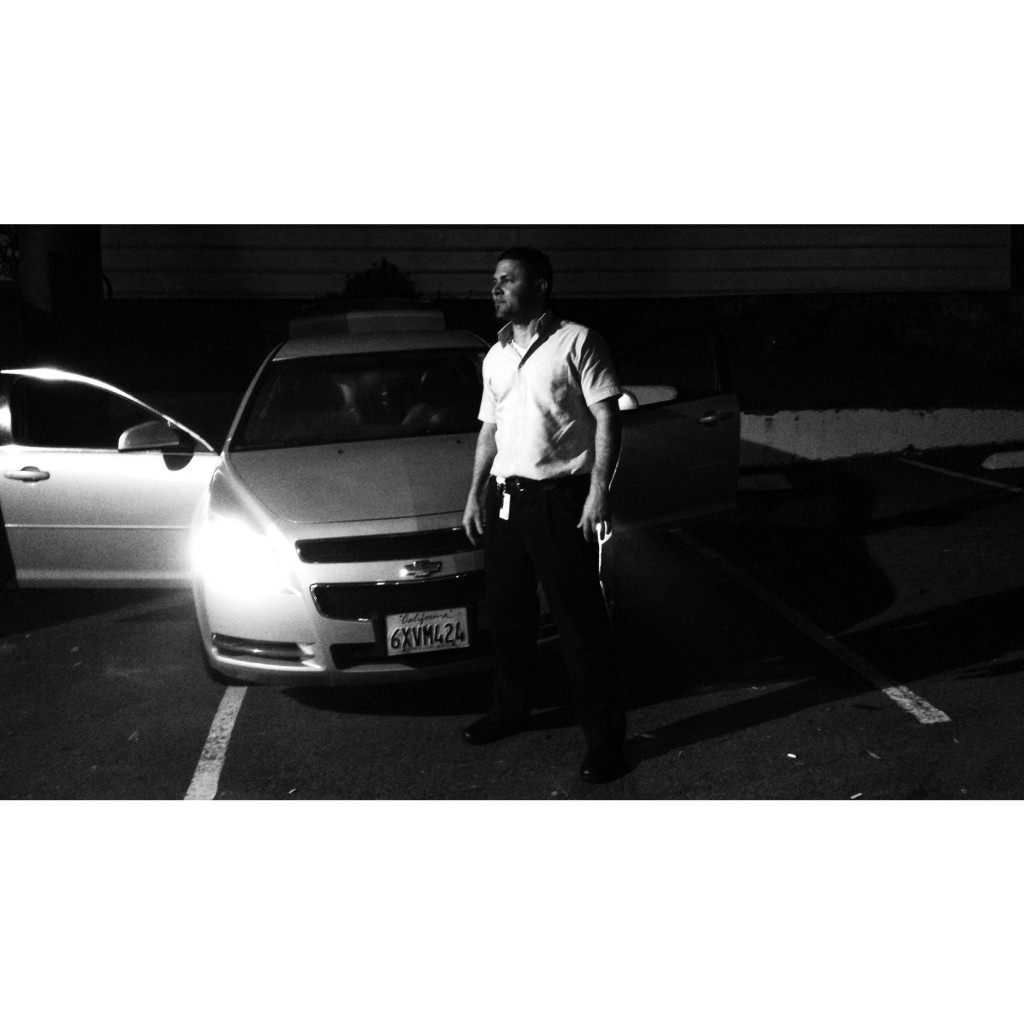

We meet Angel who was willing to stand in front of Jose’s car, whose music we could hear a full city block away. They had just gotten off work and were letting off some steam listing to some music, when I asked about the cops.

“They were just here a few minutes ago, They know we aren’t here to bother anyone, “let them make noise,” he says, quoting the cops, or guessing what they might have said just that.

A quick meal. First cup of coffee I’ve had on the project. Trying to save its power for when I really need it.

On the road. We second guess advice to stay out of the Tenderlion at this hour and wander around.

We meet a “Naomi” out working.

“You got to have a job and a hustle to make it in the city,” she tells us. There are a few others out hustling. It’s gotten a little cold and I’m starting to get tired. Keeping a watch for people keeping a watch on us.

Someone didn’t like their picture being taken, and has some words for Vlad, and Vlad has some words for them. But that’s all, just some words and we walk way. We have a deadline. The next hour. Only 18 more to go.

From the Tenderloin we head to the Ferry Building to catch the sunrise and the bridge. There is a jetty you can walk out into the the water on. That’s where Kevin is. He had the same idea we did, to watch the sunrise. He came from the East Bay to watch it. I ask if I can take his pic. “I don’t care.” He says the views here are nothing like his Midwest home. “The people are different too, they are more diverse and open minded.”

Not too long after the project, I was talking to a noted photographer about this shot. He told me that his friend’s advice to him was “don’t be that guy.” Don’t be the guy who takes pictures of people smoking. Quick little lesson: Not everyone is going to like everything you do, some might not like anything. You have do to it because you want to and I will be that guy who takes pictures of people like Kevin.

It’s fully sunny, and some part of my body is hurting. A short stop to get some water and pain meds at a very busy mini mart. Getting up or going home this early seems to hurt other people too. I’m not alone.

We hop in the car to find another place. A higher vantage point. Less people to see but the whole city to view. Beautiful. The time ticks. Deadlines loom.

This year I had the luxury to not drive. I didn’t realize how much that took out of me. Driving. The moments in the car were beautiful. Recharging my phone and me. Selecting a car shot for this hour. It somehow said more SF to me than the few portraits I took and coffee shop snaps. A green smoothie drink for early breakfast. Keeping the food light.

Back to the Mission back to the SOS Mobb. I meet Grandpa Tupac on 16th. Animated and ready to pose. One of my favorite shots of the day. Hooking up with about 10 other street photographers from the SOS Mobb including @travisjensen and @rastadave52.

A light meal of eggs and bagel- the Mission takes me back about 20 years. when I would regularly travel up to the city to visit friends. It’s changed. Changed a lot. But several times I felt as if neither the city or I had really changed at all in the last 20 years. The feelings were fleeting.

Walking from the Mission to the the Tenderloin reminded me that I was not only tired but tired of walking. Keep on. Time’s ticking. Deadlines loom.

On the walk to the TL I shot a portrait of Rasta Dave. This was a trip that couldn’t have happened without the hospitality of folks like Rasta Dave, Vlad and Travis. It’s been amazing the connections that have been made via mobile photography. I’ve met a lot of great people and learned so much from them. This is one of the best parts of The 24 Hour Project, the life connections that have been made. Getting to the the real ‘social’, of social media.

by Sam Smotherman | Feb 24, 2014 | FEATURE, Featured Articles

As the collective forgetfulness falls on the minds of the USA, Sam Smotherman revisits the killing of Trayvon Martin and the protests that erupted in response to the not guilty verdict with long time political organizer, Chris Crass to find out what can be learned to move forward to a more just society.

Protestor In Front of Los Angeles City Hall

Protestor In Front of Los Angeles City Hall

Kenny (Father) and (Son) Kai | “I brought Kai here to teach him about politics and justice.”

What was the significance of the Trayvon Martin case? Why do you think it grabbed the nation’s attention?

The murder of Trayvon Martin exposed the enduring and brutal reality of white supremacy in the United States. We heard the logic of white supremacy on the 911 call Zimmerman made. We heard Zimmerman turn a Black kid on his way home into a violent criminal. We witnessed the murderous results of Zimmerman assuming that a Black teenage boy needed to be contained and punished by any means necessary, not because he had done anything wrong, but because in a white supremacist society, Blackness equates to a pathological culture of crime and violence that must always be monitored, policed, imprisoned, and feared. It isn’t that Zimmerman acted far outside the bounds of society, it’s that he expressed the murderous, paranoid, dangerous results of the racism deeply ingrained in our society.

Systemic racism in our society that affects everything from housing to jobs to life expectancy is often denied as being a thing of the past or alternately, the result of the failures in communities of color. For example, while studies consistently show that Black and white youth use illegal drugs at around the same rate, Black youth are more then twice as likely to be arrested, and far more likely to be incarcerated.

Michelle Alexander’s best selling book, “The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness” argues that the criminal justice system in the U.S. “operates as a tightly networked system of laws, policies, customs, and institutions that operate collectively to ensure the subordinate status of a group defined largely by race.” Trayvon Martin’s murder showed the world that the New Jim Crow is the new racial order in the U.S. today.

How did protest and public expressions of outrage help make this one of the top national stories of 2013?

While the original murder grabbed headlines, what kept this story in the national spotlight, and ultimately forced the hard of the police to arrest George Zimmerman was the organized resistance of the Black community. Demonstrations erupted around the country within days of Trayvon’s murder. His family was vocal and public, and with the support of national Black leaders like Al Sharpton, they voiced outrage and grief that resonated in and beyond the Black community. Hundreds of demonstrations of tens of thousands of people took place in the initial weeks of Trayvon’s murder and this not only kept the story in the headlines, but it brought a strong race analysis to the forefront as Black people of all backgrounds denounced racial profiling and racism – from the Miami Heat basketball team to working class Black churches throughout the South.

To be clear, there were people of all backgrounds protesting the murder of Trayvon. In Knoxville, Tennessee, where I was living at the time, hundreds of white people joined with hundreds of Black people in one of the largest anti-racist demonstrations in recent memory. But that said, the organization and mobilization in the Black community is why Zimmerman was arrested, why he went on trial, and why the name Trayvon Martin is not only known around the country, but known as the name of a young man who’s life was stolen from him and all of us because white supremacy continues to shape U.S. society.

You were part of actions expressing outrage both when Trayvon Martin was murdered and when George Zimmerman was acquitted. What were you trying to accomplish and do you think it was successful?

As I mentioned before, I was living in Knoxville, Tennessee at the time of both the murder of Trayvon and the acquittal of Zimmerman. When Trayvon was murdered a coalition of groups and individuals in East Tennessee came together to form Knoxville United Against Racism. With leadership from the white, Black, and Latino community, we were able to mobilize over 400 people to express our outrage, grief, and resistance. With cities and towns around the country calling for Justice for Trayvon Martin, we brought together church groups, labor groups, LGBTQ, immigrant rights, and environmental groups, and we put forward a powerful message of unity against racism.

The Trayvon Martin murder created a dividing line in the country. Do you think Zimmerman murdered Trayvon or was it an act of self-defense? Was racism a major factor in this case or not? It is in moments like this when all of us who believe in social justice, who believe in equality, must step up and turn this travesty into a clarion call for change. Our goals were to raise awareness of the enduring reality of racism, to build momentum on the community and in society to fight racism and work for systemic equality, and to build unity across racial divisions in the process. For me, a major goal was to raise awareness in white communities and then turn that awareness into action. While there is far more that must be done, overall, I do think we were successful. Rather then Trayvon Martin’s murder being yet one of hundreds of cases of young Black people being murdered, it became a case that helped us draw attention to the epidemic of racist murders in this country. While it is true that since Trayvon, there have been dozens and dozens of horrendous murders of Black people – include several involving young Black women and men going for help after car accidents only to be shot and murder at the door of white neighbors who said they “feared for their lives” upon seeing Black people at their doors – we must do all we can to raise consciousness and get people active in the movement to end the New Jim Crow.

That brings up two important questions for me. First, how can we go from outrage of cases like Trayvon Martin and move to on-going work for social justice?

Shortly after Trayvon was murdered, I wrote the following for a national call to white people to deepen our efforts as we moved from outrage to organizing: “Let us turn our outrage and pain into commitment and action. Let us sound the alarm that silence and inaction in the face of injustice is consent and support. Let us learn from those who have come before us and get involved with those organizing for racial, gender and economic justice today. Let us be mindful of white privilege, but also remember to be powerful for racial justice. Let us act from our vision, see opportunities to challenge racism, engage in courageous efforts, create beloved community, and build our movements for collective liberation. Now is the time.”

Outrage is an important part of the journey. Outrage connects us to our sense of right and wrong and can motivate us to take action. Joining in demonstrations or organizing them ourselves is an important next step. Coming together with others in our communities is key to overcome the feelings of powerlessness and isolation, feelings which systems of inequality from apartheid, to capitalism, to white supremacy both create and thrive on. Come together with others to express our outrage, our opposition. But the next step is vital and that is the step of joining on-going efforts to win social, economic, racial, gender justice. This can be on the local, regional, national or global level, but the most important part is that we come together with link-minded people to work for positive long-term changes to the problems we face.

Shortly after the Zimmerman verdict was announced I write this short essay called, The Verdict is In: We Must Organize to Get Justice. I outline 10 steps people can take to move from outrage to organizing. Anyone who wants to explore that question further can read the essay here:

My next question is, why should white folks care about cases like Trayvon Martin? How do white folks participate in meaningful anti-racist organizing?

The question for white people is really, which side of history do you stand on? Do you stand with the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 that made every neighborhood watched by the slave patrols? Do you stand with the courts, police and juries that time and time again acquitted anyone accused of lynching a Black person? Do you stand with the White Citizenship Councils who were the most “respected” men of their community, who defended Jim Crow apartheid? Do you stand with the Klu Klux Klan who were the first to make the argument that the Voting Rights Act and Affirmative Action gave “special rights” to Blacks, an argument that quickly became a rally crying for white Americans around the country.

Or do you stand with the Abolitionists like Frederick Douglas, William Garrison and Harriet Tubman who were routinely told that they were creating racial hostility and disturbing the natural order. Do you stand with Ida B. Wells who launched an international campaign against lynching and used her skills as a journalist to expose the false accusations of rape and theft in story after story of Black men who were lynched? Do you stand with Emmett Till and his family when he, at 14 years of age, was brutally murdered by white men because he “didn’t know his place” and was supposedly flirting with a white girl. Do you stand with Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King Jr., the Freedom Riders and the Civil Rights movement as they faced angry white mobs from Chicago to Alabama?

My nephews, 5 and 7 years old, recently asked their Grandmother, at the Lincoln Presidential Library, “Nana, how could Christians have supported slavery?” It’s a heartbreaking question. And many of us who are white would respond with indignation about slavery, as we should. But how often do so many of us look back and wonder “how could people have supported slavery and segregation.” And when we look back, we are usually pretty clear that we’re not just talking about the people who actively supported, but also the people who through their indifference and inaction supported these systems. The argument is frequently made, well that was just considered normal at the time, even though it is appalling to us now. But what isn’t as frequently named is that it was the resistance of Black Americans, people of color and white anti-racists who took on those injustices and won institutional and cultural changes.

However, most white Americans would either say that they would have been on the right side of history working for justice or at the very least, they would not be on the wrong side of history supporting the slave system and segregation. But it is always so much easier to assume you would have been on the right side of history in retrospect. What is much more difficult is being on the right side of history in the here and now. Because in the here and now, we are living in the “what was considered normal,” the normal that in retrospect is so clearly racist.

The Trayvon Martin murder, and the verdict which acquitted George Zimmerman is just the tip of the iceberg, as a recent report found that in 2012 a Black man, woman or child was killed every 28 hours by police, security guards or vigilantes. It not the uniqueness of Trayvon Martin being racial profiled and killed for being Black “in the wrong neighborhood”, it’s that his story is so tragically familiar. While there have been many white people outraged by the murder and the verdict, there are many more who say “it’s just so complicated,” “they both made bad decisions that night,” “Martin got what he deserved,” or simply “the jury did a good job.”

It’s time to speak honestly. At all the points in history that we look back on and can’t understand how people supported such racism, in all those eras, white people said “it’s too complicated,” “it’s the way things are,” “that Black person must have done something to deserve it.” Even in the murder of Emmitt Till, many white people said, “it may have been extreme, but the boy forgot his place.” Today, the verdict of Zimmerman is now part of our history, but these cases continue to happen, over and over again, and white people have to choose what side of history we are on. It can be an intimidating prospect, but ultimately it is about who we choose to be as people. Our character, values, and legacies are shaped by the choices we make in the times we live, not by the stands we imagine ourselves taking in the past. I believe in our ability to stand, in the millions, in the tradition of the Abolitionists, the Freedom Riders, and the Dream Act students, the immigrant rights movement and the Justice for Trayvon Martin movement.

I believe that we can learn from white anti-racists of the past and present and make powerful and important contributions to creating a multiracial democratic society based on equality and justice for all. I recently wrote a book called Towards Collective Liberation and one of the main themes running throughout it is the process of white people coming into consciousness about racism and moving into anti-racist action. For me, anti-racism isn’t something I do on behalf of other people, it’s a struggle for the heart and soul of our society, for my family, and for myself. Racism is a cancer in white society. I organize for social justice and do this work in part because I don’t want my son to grow up to fear and hate others based on the color of their skin, I want him to grow up in the proud tradition of white anti-racists like Abbey Kelley, Anne and Carl Braden, and people I talk with in my book, contemporary white anti-racist leaders like Molly McClure, Carla Wallace, Z! Haukeness, Amy Dudley, and Marc Mascarenhas-Swan. I also do this work because I know that when we come together across divisions and work for a better world, we begin creating that new world in the here and now. We build the beloved community, that Dr. King envisioned, when we act against injustice, stand on the right side of history, join with others in our community and around the world, and work for political, economic, cultural, and social change. This is how we honor Trayvon Martin, Emmet Till, and Renisha McBride. This is how we create the world we want to give to our children and grandchildren. This is how we live with purpose, vision and values to guide us. We can do it.

Tre’ Love, Safiyyah and Safiyyah | He brought his daughter out to his first protest so, “As she grows up I want her to know when there is injustice to stand up

Ayesha Forrest | First protest | Age 13

Ayesha Forrest | First protest | Age 13

Marion The Last / Self described Pray Fast Warrior who prays that she and others gain “revolution knowledge and deliverance from evil

Marion The Last / Self described Pray Fast Warrior who prays that she and others gain “revolution knowledge and deliverance from evil

Chris Crass is a longtime social justice organizer who writes and speaks widely about anti-racist organizing, feminism for men, lessons and strategies to build visionary movements, and leadership for liberation. His book Towards Collective Liberation: anti-racist organizing, feminist praxis, and movement building strategy was recently published by PM Press.

by Sam Smotherman | Oct 3, 2013 | Stories

Raymond by Sam S

Raymond | “Dad can we go down that alley?” my daughter asks. “Sure.” We cross the street, which is closed to traffic as there is some sort filming going on, we squeeze between a moving van which is blocking the entrance to the ally and this is were we met Raymond. His shopping cart in the middle of the alley way piled with various bits of salvageable materials he was hunched over a dumpster looking for more. A polite man, he had overlooked my son kicking a box of his filled with plastic bottles. He would later prove himself to be a gracious man, forgiving my son, for proudly finding a dead rat a presenting it to us on cardboard plater. “Get it away get it away!” He shouted at my boy. After helping my son put the dead rat down and out if sight. I apologize to Raymond who dismisses my apology, “He’s just being a boy…he reminds me I my nephew.” “But he has to be careful. I’m always really careful, I just don’t sticky hands in here,” he says looking again for scraps of metal in the dumpster, “there are dirty needles in here.” “There are a lot of heroin addicts around here, he says looking up and around pointing at the various buildings that create the valley were we stand. “I should know there are a lot. I go through their trash.”

But before the dead rat Raymond and I were talking about life. In his 60s and recently homeless for the first time, “I made some bad decisions.” He did not elaborate and I didn’t ask. While we talked he was always moving always working.

He talked about being grateful. “I pray everyday and give thanks, but I can’t ask God for help and then not go and do anything…this stuff is here for me to take,” holding up a small scrap of metal, “I believe that God helps those who help themselves.” “I don’t ever want to be like those people in the wheelchairs, on Skid-row, who think that every body owes them something.” “I’m always grateful for what I have…you have to be grateful.”

I ask him if had family around to help him. He mentions family scattered over countries, states and cities but that they help, “when I let them.”

Protestor In Front of Los Angeles City Hall

Protestor In Front of Los Angeles City Hall

Ayesha Forrest | First protest | Age 13

Ayesha Forrest | First protest | Age 13 Marion The Last / Self described Pray Fast Warrior who prays that she and others gain “revolution knowledge and deliverance from evil

Marion The Last / Self described Pray Fast Warrior who prays that she and others gain “revolution knowledge and deliverance from evil

Robert Frank

Robert Frank