by Grryo Community | Dec 22, 2017 | Antonia Baedt, George Pavlopoulus, Romina Mandrini, Simran I. Nanwani, Stories, Storyteller, Susanne Maude, Tommy Wallace

What does a Grryo Christmas look like? We asked each member of the Grryo Lead team to share their heartfelt experiences…

Romina’s story

For me, so much about the Christmas season is about the sacredness of time. As soon as December arrives, I am hit with an avalanche of farewell dinners, end-of-year concerts and school functions, all while manically trying to buy gifts for family and friends. Time speeds up, it would seem, and I often feel breathless from the sheer momentum of it all.

Time…

As I say goodbye to colleagues, watch my children graduate to a new school year and write cards to loved ones, I subconsciously whisper my thanks and farewell to the year that’s passed and to everything that has been.

And then, finally, time slows down again, as the rush draws to a close. I savour the gifts of cooking, chatting and laughing with family and friends before I turn my eyes to the time that lays ahead: a brand new beginning brimming with possibility.

Susanne’s story

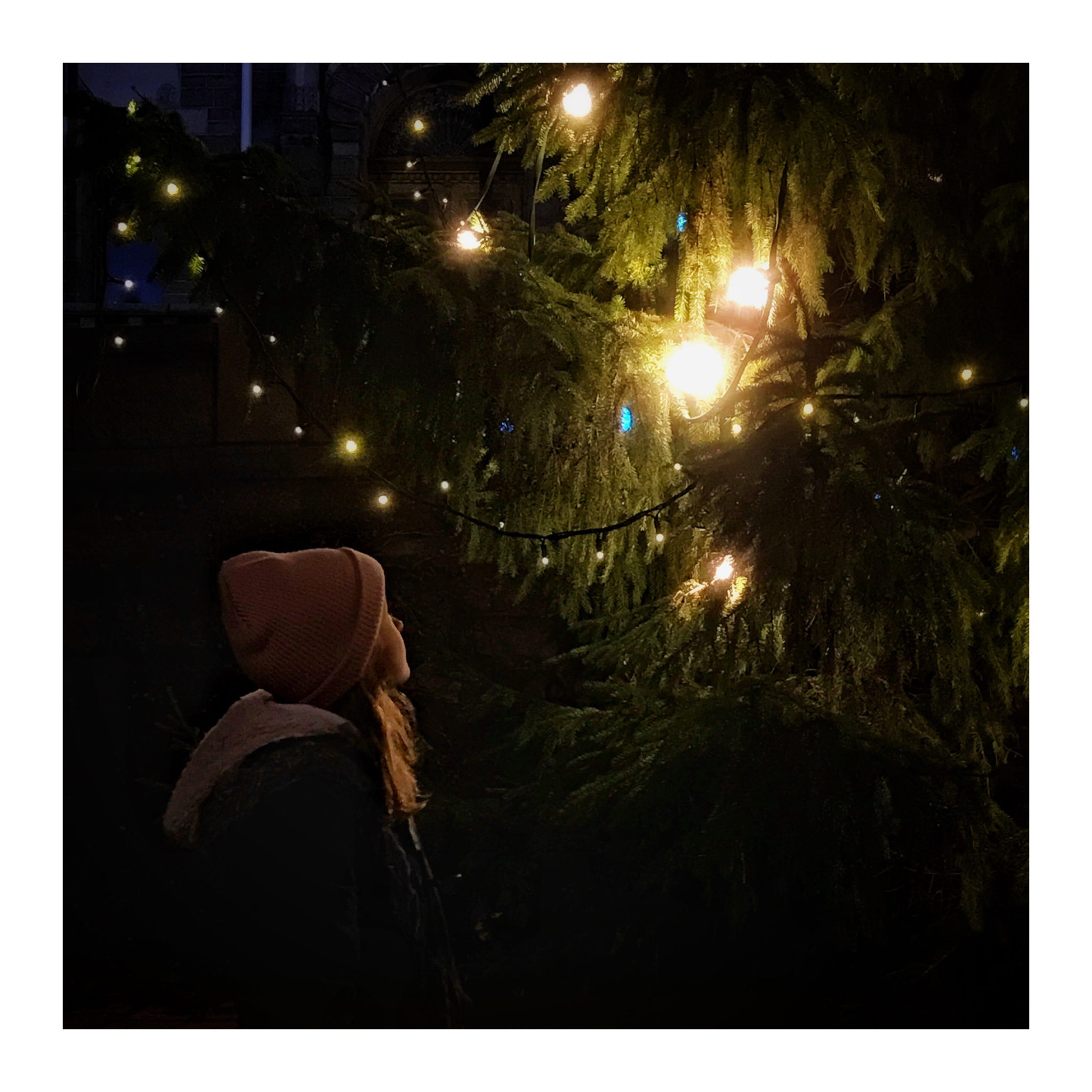

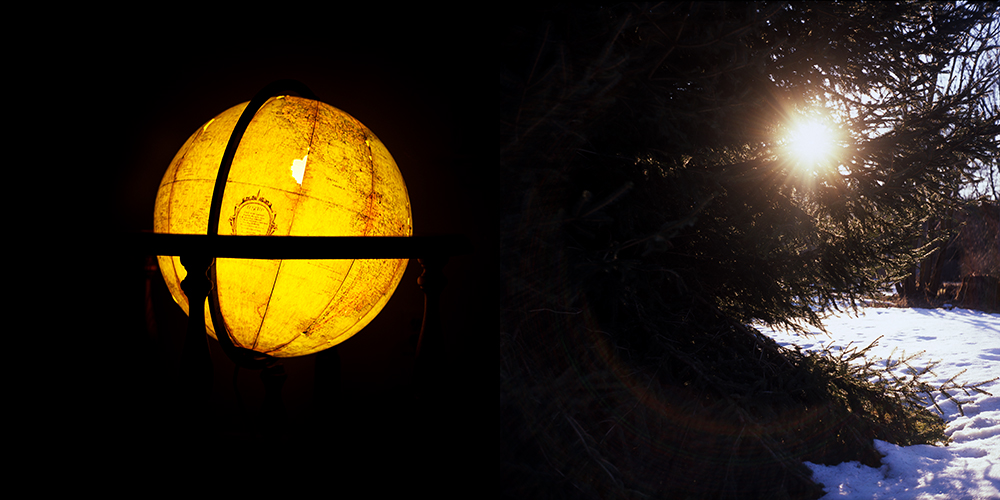

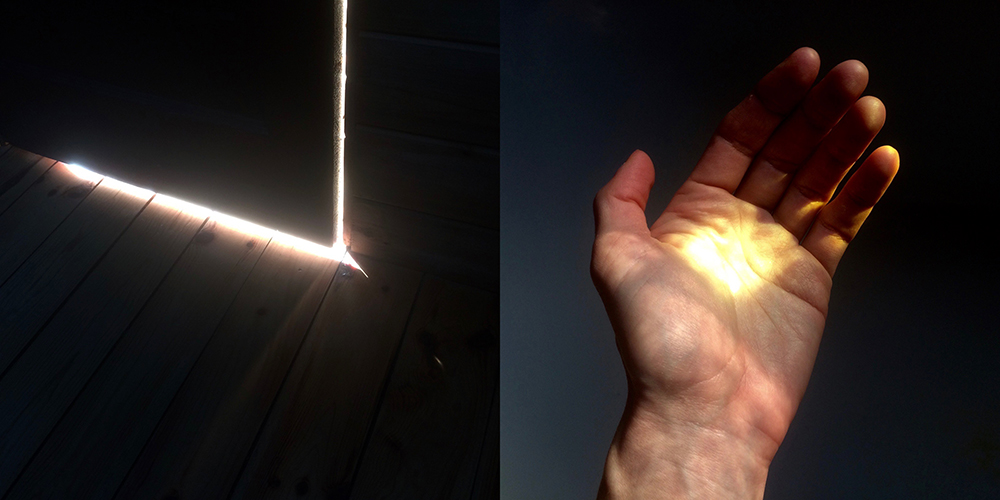

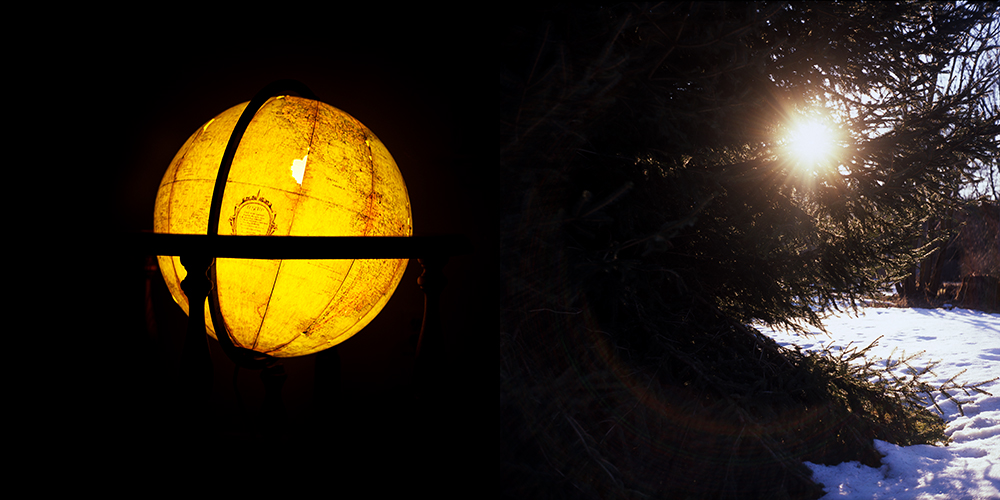

I cherish all the light that Christmas brings to the darkest of the months.

When days are short and nights are long, we fill December with stars and candles. And then darkness no longer feels like an enemy.

Christmas means time spent with the family. We sleep longer, close our laptops and phones, bake gingerbread cookies, play board games and relish traditional Christmas food. My kids, especially the younger one, are looking forward to meeting Father Christmas again on the 24th, Christmas Eve. Father Christmas lives in Northern Finland, in Lapland, in a place called Korvatunturi (Ear Fell in English), where he has his secret toy and gift workshop.

Antonia’s story

In December my world is dark with city lights and rain. Christmas means too much office coffee and the sound of the city’s traffic on wet streets. It’s the time of the year when I am all caught up in my job while days are short and daylight is sparse. It produces a feeling of abstraction, like being a detached island in a sea of hectic gift buying, baking, cooking, traveling and doing all things Christmassy. I enjoy watching the circus and love to dip a toe in when I join the merry masses at Christmas markets and dinners with friends and colleagues.

When daylight is the city lights, and tires on wet concrete is the soundtrack. @tonivisual

Out there we fight the darkness with lights and sugar. The cities wear their Christmas markets like a scratchy, favorite winter garment. Renditions of jingle bells fill the air and the smell of Glühwein (hot spiced wine), anise, roasted almonds and melted chocolate lingers wherever you go.

It even seeps down into the catacombs of the subway stations where commuters are joined by herds of shoppers and people dragging their live Christmas trees up the escalators.

On Christmas eve, I leave my island and join my family for cooking goose, the big Christmas tree with real wax candles and cozy nights with board games by the fire.

“lone man in the subway station” – the feeling when the season’s circus is all around but you’re not in it yet. @tonivisual

Tommy’s story

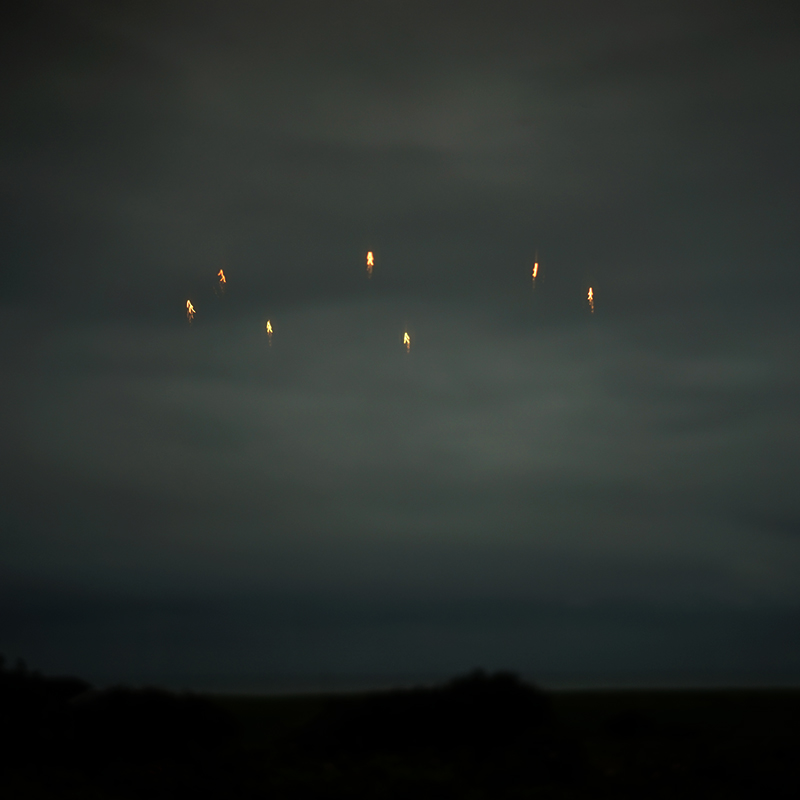

Every Christmas is different. Family changes. People grow older. Children grow up. A wedding takes place as two lives become one. A grandson will experience his first Christmas. My fourth Christmas with Grryo will be my last.

Every Christmas is the same. Family gathers. Friends share the joys of the past year while at the same time we always find something new to celebrate. We all experience some childlike wonder even though our hair starts to gray. And the richness of story, which is the core of Grryo’s purpose, stays with us always.

Merry Christmas!

George’s story

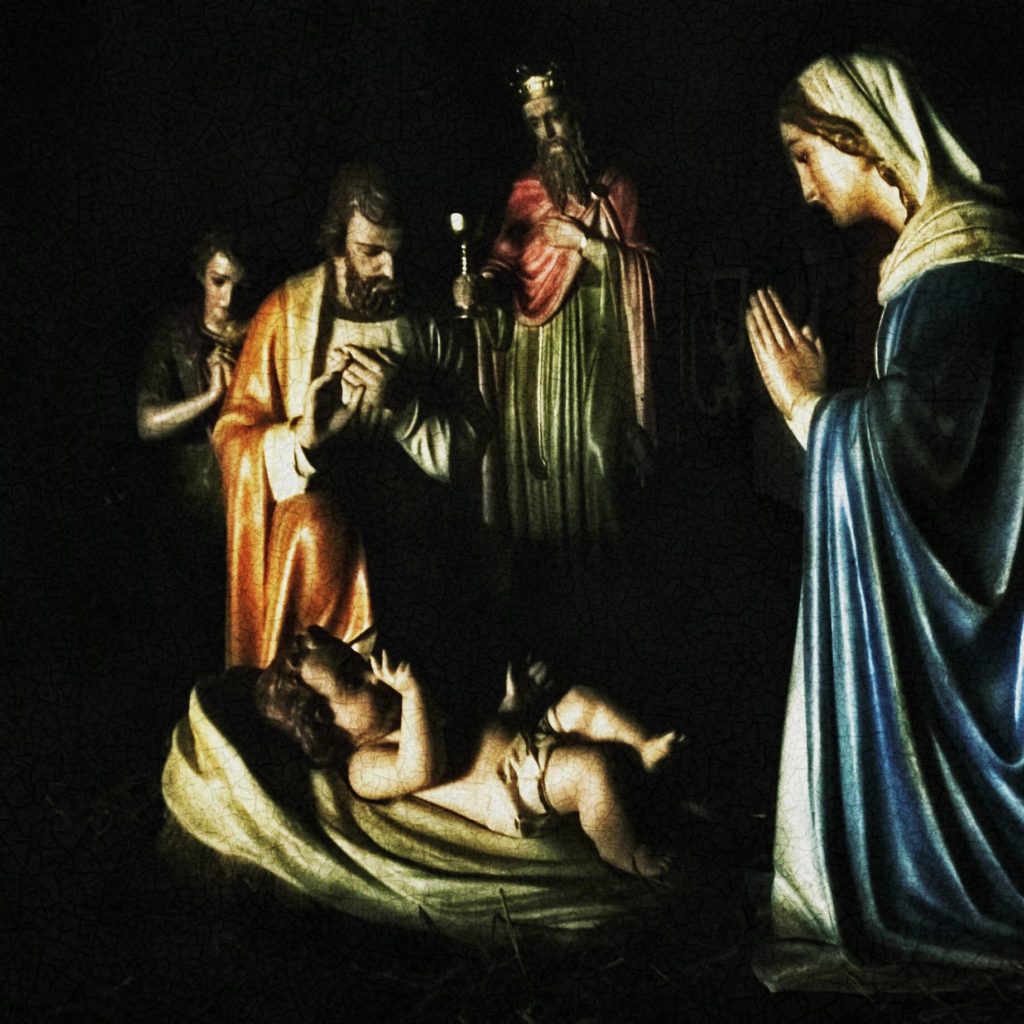

Around the Christmas table, I try to remember what have I lost and what have I gained during the past year. I tend to get extremely bored in family dinners and given the melancholy of the days I’m usually the one searching for excuses in order not to attend -the excuses always fail and I eventually attend the dinner. I avoid shooting photos with a camera or a smartphone and I only take instant photos with a Fuji Instax. The prints find their way straight into a box and I check them again after weeks or even months. There is a certain weight in religious celebrations that I am always unwilling to carry. The only fun thing is setting some goals for the coming year. There is usually an overload of goals and usually around February they vanish into thin air. I can’t give you any good advice regarding setting goals, but if I had to, I’d just say set a single goal for 2018 and try to achieve half of it; this seems already enough.

Try to spend some quality time with your beloved ones. Even in the most boring dinners, there might be a sentence that will change you a bit. Use it as a chance to remember a day that for some reason everybody seems to appreciate. And remember your last year’s dinner and compare who was around and who might be absent. I am usually more happy about past year’s dinners than the coming ones. I remember the faces, the family table, the food. Last year it was the last Christmas dinner with the grandma; she won’t attend any of the future ones. Drink some wine, appreciate the presence of people and their presents too. And get slightly bored: this seems to me as the last shelter of creativity.

Simran’s story

The word ‘Christmas’ fills our minds with snow, winter, Christmas decorations, joyful carols and various savored baked goodies. As it isn’t very Christmassy spirit on my side of the world, I choose to count my blessings as the festive season approaches and the year ends. Every year brings its challenges but we make the choice of whether we want to complain or appreciate our moments. Gratitude allows us to live in the present moment and continue to see the light by moving forward.

It has been a good year for us at Grryo. We have started to grow slowly but surely with beautiful stories that keep us amazed at the huge talent that exists. As we share our Christmas stories at Grryo, where all of us live in various parts of the world, we celebrate it by making use of the digital world. It is remarkable what technology can do when used productively.

The connections and relationships we have weaved together at Grryo, have made us feel like a family even if we have never met one another. I truly appreciate and value each one of them. It has been a great pleasure building friendships with all of them. Let us cheer for the jolly season and be hopeful for the blessings in the coming year ahead!

The Grryo team would like to sincerely thank you for making 2017 a great year of stories shared! Whether you wrote stories or read them – or both! – a very big thank you for your continuous, amazing support. We wish you safe and happy holidays. Looking forward to more of your wonderful stories in 2018!

by Romina Mandrini | Dec 21, 2016 | Romina Mandrini, Stories, Storyteller

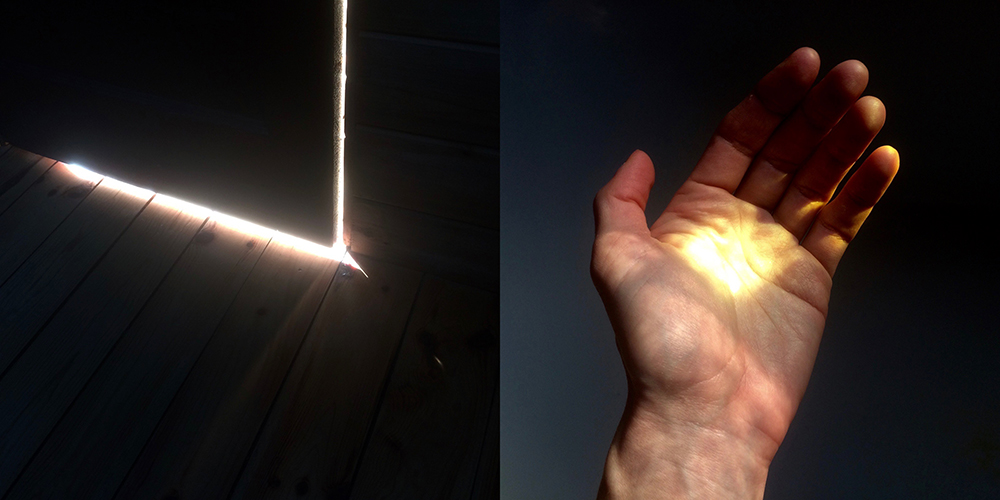

“If you wish for light, be ready to receive light.” Rumi

As the season of gift-giving fast approaches, I’ve been thinking about the gifts I’ve received this year – images graciously given to me by my trusty old camera.

I’ve been interested in the practice of contemplative photography for a while now, and through it, continue to discover new and surprising things about this craft. A few years ago I came across The Little Book of Contemplative Photography by Howard Zehr, a book I have come back to again and again, not only because it is a quick and easy read, but because of the wisdom contained in its pages.

There is a particular chapter in this book that continually challenges me and makes me rethink my approach to photography. In this chapter, Zehr discusses the language and metaphors of photography and how aggressive and predatory they are. History shows that photography was once considered a gentle and respectful art, but its image as an art form became much more aggressive when small handheld cameras were introduced in the 1880s. It was around this time that people started going on photo shoots, carrying their arsenal of equipment, aiming their camera, taking their pictures and capturing their subject…metaphors that gradually became deeply embedded in our culture and consciousness. Before long, advertisers were marketing camera products that would ‘shoot to kill’ and camera store services that would ‘blow you away’. We began to use telephoto lenses and, more recently, smart phones to covertly photograph people. This shift, where the act of photographing became something of a hunt, has had a massive impact on the way we practise photography today.

When I first read about this idea, I’d been learning photography for a couple of years, so naturally I began to consider this in relation to my work and my process. I’d certainly been striving to ‘capture’ my children with my camera and getting frustrated when I didn’t get what I wanted or when I got something ‘wrong’. This put me in the position of taker, not receiver, and of triumphant predator when I did get something ‘good’.

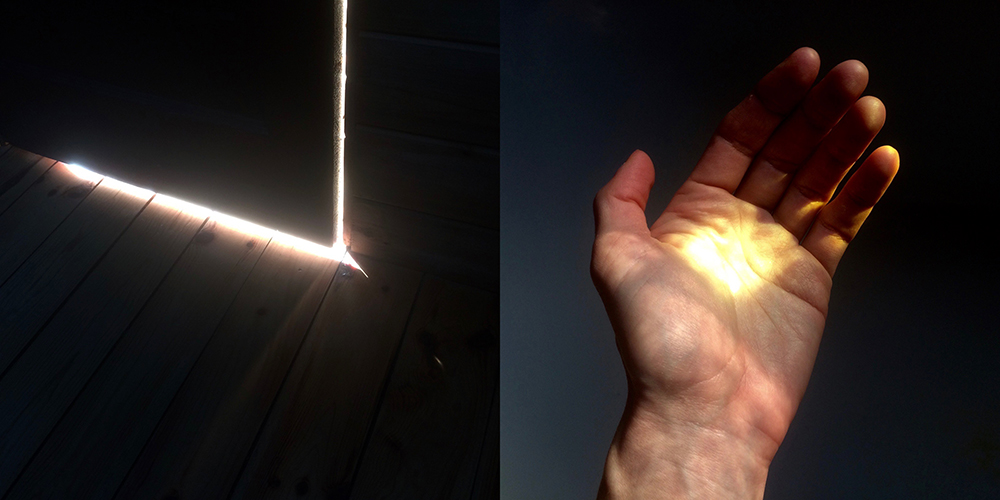

But, the reality is, as Zehr quite simply points out, that when we photograph, we do not actually reach out and take anything. Light is reflected off our subject and enters through our camera’s lens, projecting a picture. So, essentially, the image is being received, not taken. And for me, here lay a secret to experiencing photography in a new and more profound way: I could open myself up to receiving images; I could change my perspective so that I no longer viewed images as trophies, but as gifts.

So where did this leave planning a conceptual photo session or the discipline of hunting out and capturing an image? Exactly where they belong, in their perfect time and place. Because whatever the situation, as we stand behind our camera we have an opportunity to experience new possibilities. We can do that by recognising that there is so much more to photography than our skill and our equipment – or, as Zehr so aptly puts it, we can shift our perspective so that we approach our art making with ‘wonder, respect and humility’. In other words, instead of seeing photography as a conquest, we can see it as contemplation; instead of seeing it as an exposé, we can see it as a revelation; instead of being concerned with control, we can embrace surprise.

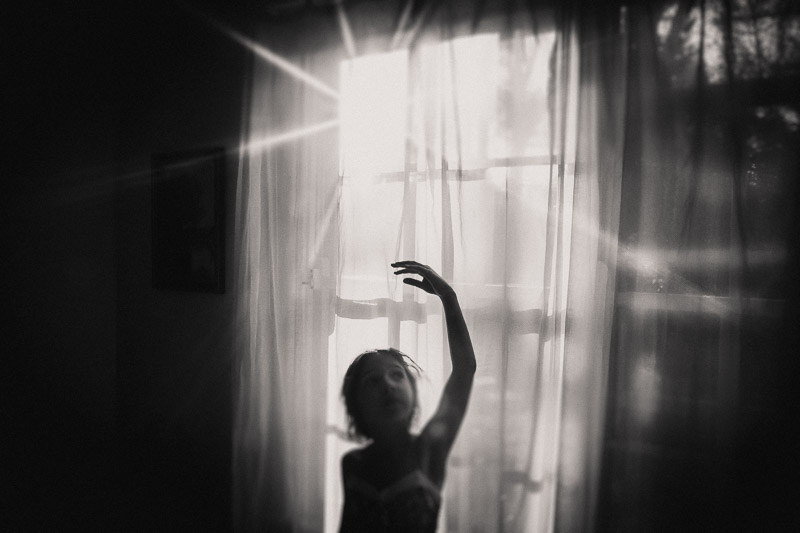

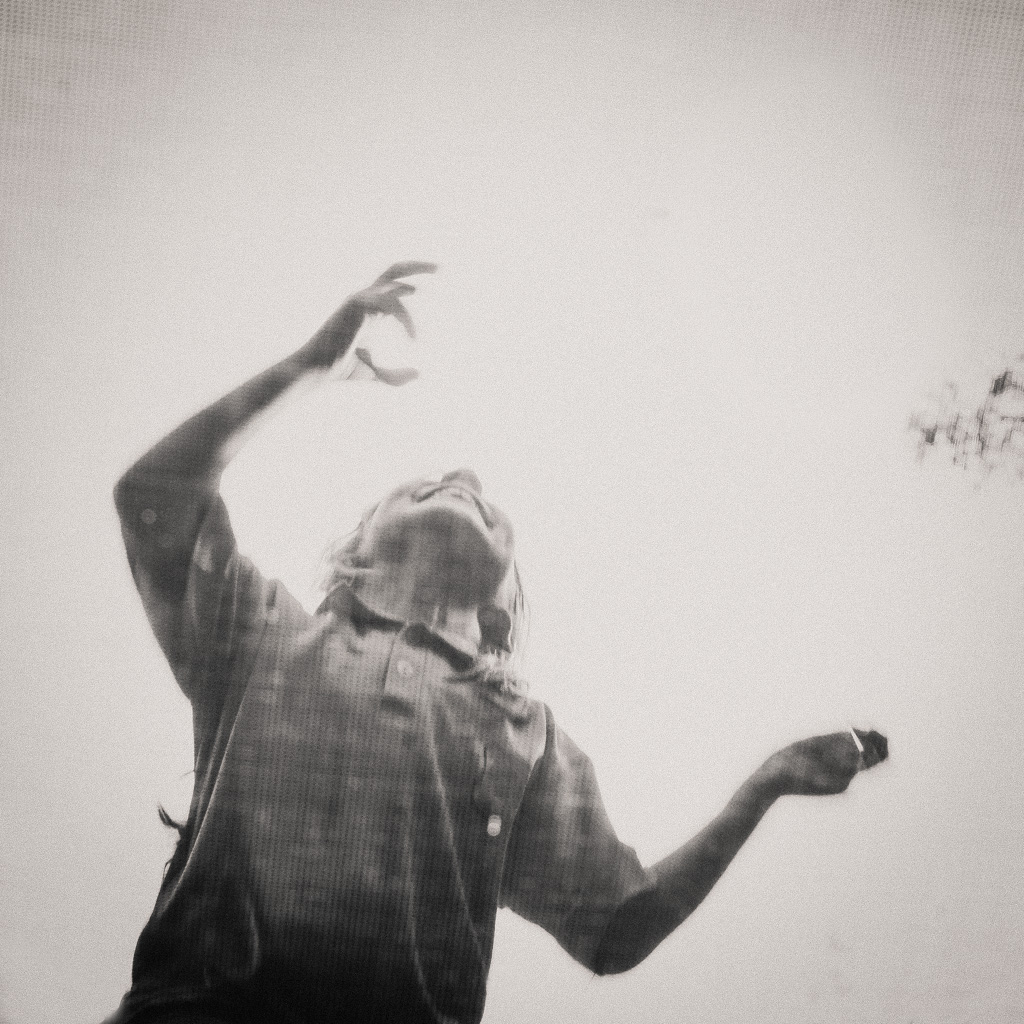

No doubt, we’ve all experienced photographic surprises – sometimes by sheer accident (like when we unintentionally press the shutter) or sometimes simply because an image was unexpected (like when we think we didn’t ‘get’ anything good, but are later surprised to find that we did). But what interests me most is not this lack of control; rather, this concept of awe and humility, as a mindset and approach towards art making in general. By visualising myself receiving rather than taking images, I have been continually taken aback by what light has revealed inside my camera. I’ve relaxed. I’ve opened myself up to mystery. I’ve not always been given what I wanted, but what needed to be expressed was expressed in a new and surprising way. This surrender has become a very sweet part of my practice. Because it’s not only the unexpected images that are gifts – they are all gifts.

Of course, this change in attitude is easier said than done. Ironically, it takes a form of conscious effort to remember to let go, and even now, though I’ve intellectually understood the concept, I sometimes fall back into rigid ways of thinking. But whatever happens, the intention is set: to place myself in a position of receptivity and be surprised by what’s out there. As Jay Maisel once said, ‘The pictures are everywhere. If you’re open, they will find you.’ I try to be aware but not anxious because, at the end of the day, I am just a tiny part of the equation. There is something bigger, more magical and mysterious that takes place when my hands get a hold of the camera – something I can’t actually control.

I was recently amazed to discover that one of my favourite photographers, Sally Mann, had made references to this mystery and magic, and that she herself viewed photography as a humble act of receiving. In Immediate Family, she wrote, ‘At times, it is difficult to say exactly who makes the pictures. Some are gifts to me from my children: gifts that come in a moment as fleeting as the touch of an angel’s wing. I pray for that angel to come to us when I set the camera up, knowing that there is not one good picture in five hot acres. We put ourselves into a state of grace we hope is deserving of reward, and it is a state of grace with the Angel of Chance.’

And so, as the year draws to a close and a new one begins…whether you are a street photographer or a still life photographer, whether you photograph landscapes or your own family, and no matter what camera you use…there are gifts waiting for you. Be open to receiving them, and they will find you.

by Romina Mandrini | Jul 12, 2016 | Romina Mandrini, Stories, You Are Grryo

In Spirit and Truth: An Interview with Laura Valenti by Romina Mandrini

A couple of years ago I enrolled in a six-week online photography course that would impact me – both as a person and as an artist – in ways I never could have imagined. This workshop not only challenged a lot of the pre-conceived ideas I had about photography and art making, but was also the impetus behind a profound journey of self-discovery.

The course was Candela: Finding Inspiration Through Photography, and it was taught by Laura Valenti. Laura is a photographer, curator and educator from Portland, Oregon. She is also the Outreach Director for Photolucida, a non-profit organization that aims to build connections between photographers and the gallery and publishing worlds.

Recently, I had the pleasure of asking Laura a little more about herself, her work and her philosophy.

Image by Fritz Liedtke

As a child you lived in Asia. Tell us a bit about your cultural background and how you grew up.

I spent my first fifteen years in Korea, Japan, and Hong Kong. Because I had such a transient childhood, it took me a long time to develop a sense of place like many other people have. I didn’t have roots in any particular place. My family used to say, “Home is where the furniture is!” It wasn’t uncommon for us to wake up in the middle of the night and not remember what country we were in, or what the house around us looked like. Over time, I learned that I do have a sense of place – I just carry it with me wherever I go. This concept has made its way into my photographic work, actually. I often photograph scenes that express a sense of home, comfort, and belonging.

What attracted you to photography in particular, as opposed to other forms of art making?

I really don’t know what drew me to photography, though I’ve always had a penchant for artsy, crafty endeavours. My father had a darkroom in the basement, so I was lucky to see the magic of the process at an early age. I know I desperately wanted my parents’ camera when I was very small. I keenly remember my mother allowing me to use it one day when I was five years old, and I remember taking my very first picture. I took pictures when we were out and about in Seoul, I photographed friends at birthday parties, and I set up my stuffed animals in silly little tableaus. The camera shot square images and came equipped with exciting flashcubes. Today I still shoot square format, so you could say I’ve stayed true to my original vision.

You have a deep interest in the intersection of mindfulness and the creative practice, and your focus is very much on the process itself rather than the end product. What are some of the ways in which you apply mindfulness when you are photographing?

Mindfulness and the creative practice are interrelated in so many ways. It’s been said that mindfulness is about deepening the quality of our attention, and photography definitely does that. As a practice, photography can help us to be present. When we look around the world for interesting subjects, hone in on particular compositions, and thoughtfully set our cameras – that can all be an opportunity to slow down and practice mindfulness. Photography can be a meditation, in a way. So yes, process feels very important to me. I also like to use joy as a metric when photographing. Are your process, technique, and subject making you joyful? If so, you’re doing it right. A joyful, enriching process leads to stronger images.

How does your spiritual practice influence your work?

A lot of my images are an investigation of the idea of impermanence – a core Buddhist concept. When I recognize how fragile life is, it makes me appreciate it so much more. So, I make images to celebrate my body as it changes, to celebrate the beauty of changing light, to honor transient, transformative moments, and also to mark times when I feel particularly connected to my experience. I like images that are underpinned with depth of meaning like this.

Through my images, I’m also exploring how exquisitely beautiful, painful and joyous life can be – often all at the same time. Even awful experiences are occasions for insight and growth – and the creative process can be a cathartic way to come to terms with challenging life experiences.

One of the concepts that impacted me the most when I took your course was the idea that all photography is essentially an exploration of self. Was there a particular moment in your life when you distinctly realised this?

When I was nineteen I taught darkroom one summer to a group of “at-risk” teens through a great program called Youth In Focus. The kids photographed their home lives, and I remember seeing some pretty edgy pictures. But, the pictures were much more emotionally powerful than they would have been if they had photographed scenes they had no personal connection to.

When I curate exhibitions, I’m always most drawn to images that show the personality of the artist. I want to see artists really put themselves on the line to make their work. I want to see images that are vulnerable, open, emotional. When people make photographs that are deeply informed by their immediate life experience and emotions, they’re almost always stronger. That’s not to say that all photography should be explicitly autobiographical, but I do think images should reflect the passions and personality of each artist. Who you are matters.

Writers are often told to “write what you know”. It’s good advice for visual artists, too. We have backstage passes to our own lives, essentially. Of course, it can be scary to photograph from a place like this, but when photographers realize their photographs are less about the external world and more about their internal climate (and how they relate to the world), their work gets much more interesting.

A very good example of this, of course, is your series “The Family Home”, in which you pay homage to the house your father grew up in. Can you tell us a bit about this body of work and how it came about?

My grandfather died and his wife was preparing to sell the home. I went back, knowing it would be my last visit. It was a special place for me. I moved every couple years as a child, but visited that house almost every summer. So, it was a nostalgic, significant spot. I wanted to make images that honoured the place and my memories.

It was also a sad place, because the neighbourhood was a “cancer cluster”. Something was wrong that caused an inordinate number of people in the neighbourhood to get cancer. It affected my family too. I wanted the images to touch on the pain of loss as well as the beauty of nostalgia for home. I’m so glad I did the portfolio, since it’s my only tie now to those rich childhood memories.

As a juror and curator, you are constantly surrounded by other photographers’ images. Do you ever feel this gets in the way of your own ideas and style?

I really enjoy looking at a lot of work. It feels like a privilege to regularly be exposed to such a wide diversity of contemporary photography. It keeps me visually educated and inspired. Surprisingly, I don’t get visually overloaded, even when jurying a competition with 1000 entries. If anything, looking at a lot of work makes me feel like a stronger photographer. It gives me a better sense of what I like and don’t like, greater confidence in the direction of my work, and a fuller awareness of what is truly unique in the photo world (and what is overdone). When photographers are unaware of these things, it shows. Visual literacy is critical. Photography is like a language. We can express simple ideas with a basic grip on the syntax, and we can express more complex ideas (even poetry!) with a more fluent, nuanced understanding.

Finally, what makes a great photograph?

I care more about meaning and emotion in a photograph than about its technical perfection. I’m interested in images that really make me feel something. Technical mastery is important, of course, but if the image lacks emotional power, it just falls flat.

Most photography education focuses on the technical, and photographers are often taught that they need a lot of fancy gear and an exhaustive knowledge of post-processing programs in order to make images worth caring about. That’s just not true, and I think this prioritization of technique over vision does a disservice to photographers.

Photographers who just study technique for years and years often wind up feeling like they’ve missed some of the magic and beauty that sparked their interest in photography in the first place. Technical education can feel soulless after a point – but the arts are bursting with vibrancy and soul. So, I’m interested in opening up this conversation when I teach. I’m interested in talking to photographers about moving beyond the technical and doing the deeper work, investigating what it really means to be an artist. That’s the way to set the stage for great images.

You can find out more about Laura’s online courses and in-person retreats – as well as see more of her work – by visiting her website (www.valentiphotography.com). You can also find Laura on Fcebook and Instagram.

by Romina Mandrini | May 9, 2016 | Romina Mandrini, Stories, You Are Grryo

I discovered photography around four years ago…or perhaps it is photography that found me.

It all started with some very severe sleep deprivation. Some might even say I was delirious at the time. I’d recently had my fourth baby, and to say he didn’t like to sleep is an understatement. Not. A. Wink. It was sheer torture, day after day, month after month, and it seemed endless. But it was during this bleary-eyed haziness that I felt something explode inside of me. I remember it so clearly, almost tangibly (and believe me, I do not remember much from that time). Creativity started pouring out of me, like lava from a volcano. I began painting and making collages, almost manically. Silly little works to me, as I certainly did not perceive myself as an artist. Creating something – anything – gave the sleeplessness some worthy purpose.

The Parting

As a child I’d been very creative, enjoying reading, writing and painting. I longed to study fine art after high school, but my art teacher laughed at me and said I was more suited to studying psychology. I was mortified, deeply embarrassed. I’ll never forget the humiliation. How could I have got it so wrong? How could I have dared to imagine that I could be an artist? I decided to study literature at University (I took some psychology classes too – ha!). I went on to work as a children’s book editor, a job I loved. I thought I’d found my calling, helping others tell their stories, working behind the scenes.

In Hiding

The Burial

All along, though, there were stories that I needed to tell too. On a whim during this sleep-deprived-but-creative phase, I found myself buying a used DSLR – a Canon 30D. Looking back now, I don’t really know why I did this, but I can only guess it was another effort to save myself from the sinking ship I was on. I started researching like crazy, learning everything I could about photography. I enrolled in online courses, watched tutorial after tutorial till all hours of the night. I was utterly exhausted, but at the same time completely energised by this newfound obsession. Making images – expressing myself in a visual way – made me feel alive. It was like being reunited with a long-lost friend.

Stronger Than She Looks

Reunited

At first I was simply documenting our family life. I was happy just to be able to capture light, to produce an image that matched what I envisaged in my mind. But soon I began to get a niggling feeling that producing a “pretty picture” wasn’t quite enough. There had to be something more. I started reading about contemplative photography as a way of producing more meaningful images. This mindful approach really struck a chord with me and I began to put some of its techniques into practice.

Eye of the Heart

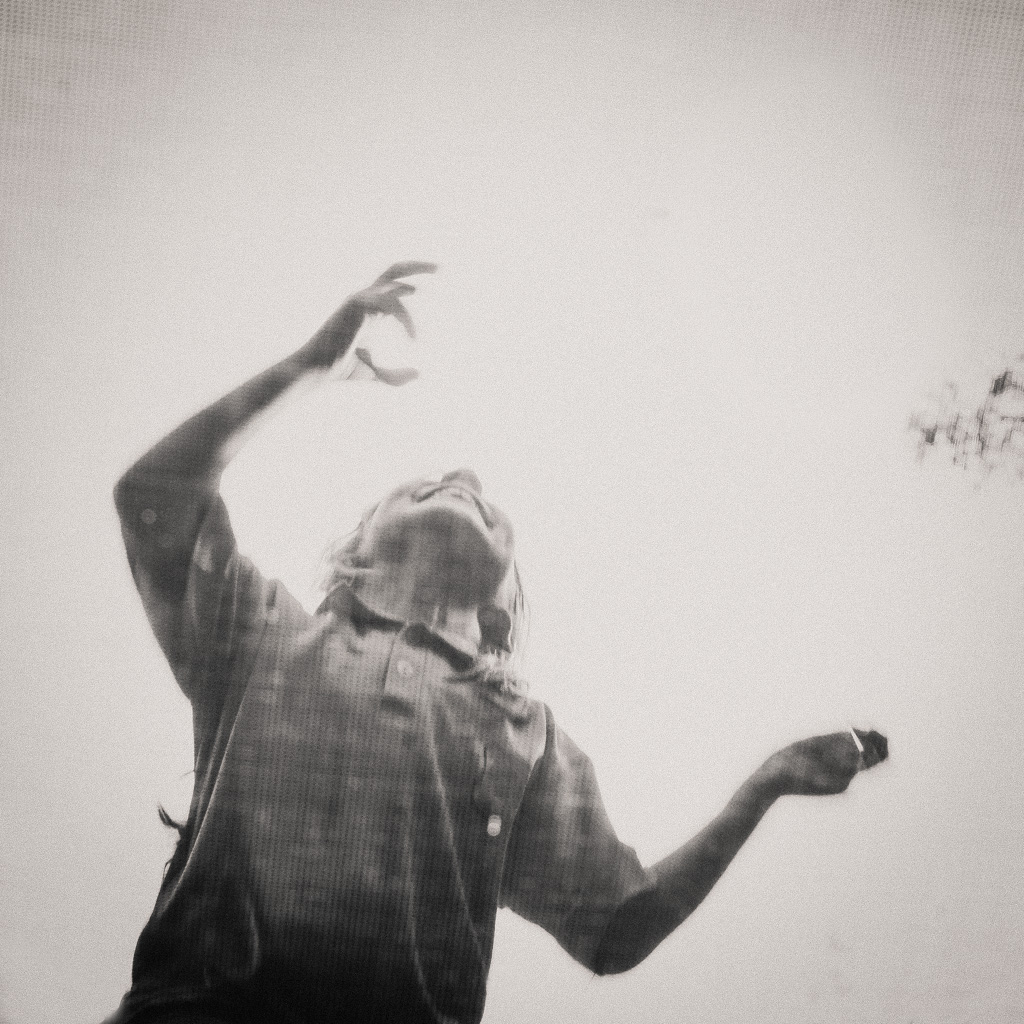

One day, about two years into my photography journey (and sleeping much better by now!), I made a startling discovery. I was browsing my Lightroom library, when it suddenly hit me. Images jumped out at me, like embers from a fire. I was shocked to see that what I was really photographing was not just my children – it was me. I could see my own childhood, my own pain, my own emotions in the images. I could see how my creativity had been buried beneath my insecurities and, dare I say it, shame. At first this revelation was somewhat disturbing. It was a bit like being given a new pair of glasses, looking in the mirror and suddenly seeing all the ugly imperfections that you never knew were there. I remember at one point thinking I might not be able to pick up a camera again – it was too painful to face myself in that way. I could hear that old storyline echoing in my mind – “you’re not cut out for this”. But despite myself, I started feeling incredible healing taking place.

Finally Seen

Since that moment, I’ve looked at photography in a completely different way. I’ve stopped striving to “take” good photos; rather I feel excited to see what images I will be given. My images have taken on a new meaning. They continue to tell me stories about myself, revealing secrets I didn’t even know I was keeping. Often it’s in the little in-between moments, in the photos I would otherwise reject as “mistakes”. Other times it’s in the gems. Furthermore, an image may reveal something to me today, and months later it may reveal something new. It’s almost as if each image has an endless number of stories in it.

Roots

Playing With Light

These days I photograph with a Canon 5D and an iPhone 6. Since joining Instagram a few months ago, I have been moved and inspired to find a whole community of people courageously sharing their stories with me. In the process, I have been encouraged to learn that others find meaning in my images too. This has been a most rewarding and humbling experience.

Escape from the Cage

Soar

Dorothea Lange once said, “A photographer’s files are, in a sense, his autobiography”, and I don’t think she was necessarily referring to documentary photography, which was her genre. I think there are stories being revealed in all photographers’ work. I encourage you to look more closely at yours. You never know what secrets you will find.

Quiet

You can see more of Romina’s work on Instagram and Flickr.